Heart full, wide open

The weather has been unforgiving since I got here; dark mornings using my watch’s flashlight as a beacon of light that signals my steps, my sweaty curls getting frosty and crusty along the way, blocks of snow piled on the sides of the road, and the crisp cold burning my legs until red and numb; the altitude humbles me once again, it forces me to slow down and enjoy the view, the never-ending hill says to me, “don’t stop until you get to the top.”

I’m back home.

I’m back on the roads where it all began; I picture my young self running behind, wearing some standard trainers, an old T-shirt and some ragged leggings, holding an MP4 and moving my arms between some wired headphones. No watch, no Strava, no sense of pace at all.

I’m back home. My long sleeve covering my watch and ahead of me a lonely, narrow, and winding road; I’ve left the house just thinking about going, just thinking about taking myself far and with no specific goals. The empty landscape opens up to my gaze, a sense of expanse in motion, the mountains steering the way.

Wide open, heart full. Can’t see the watch but I can see where I’m going.

The new year is just the next step forward, I’m running on the same road: stronger in my heart, more confident in my voice, yet still a learner, still that young girl wanting to embrace the wide open, to leave the house and just go.

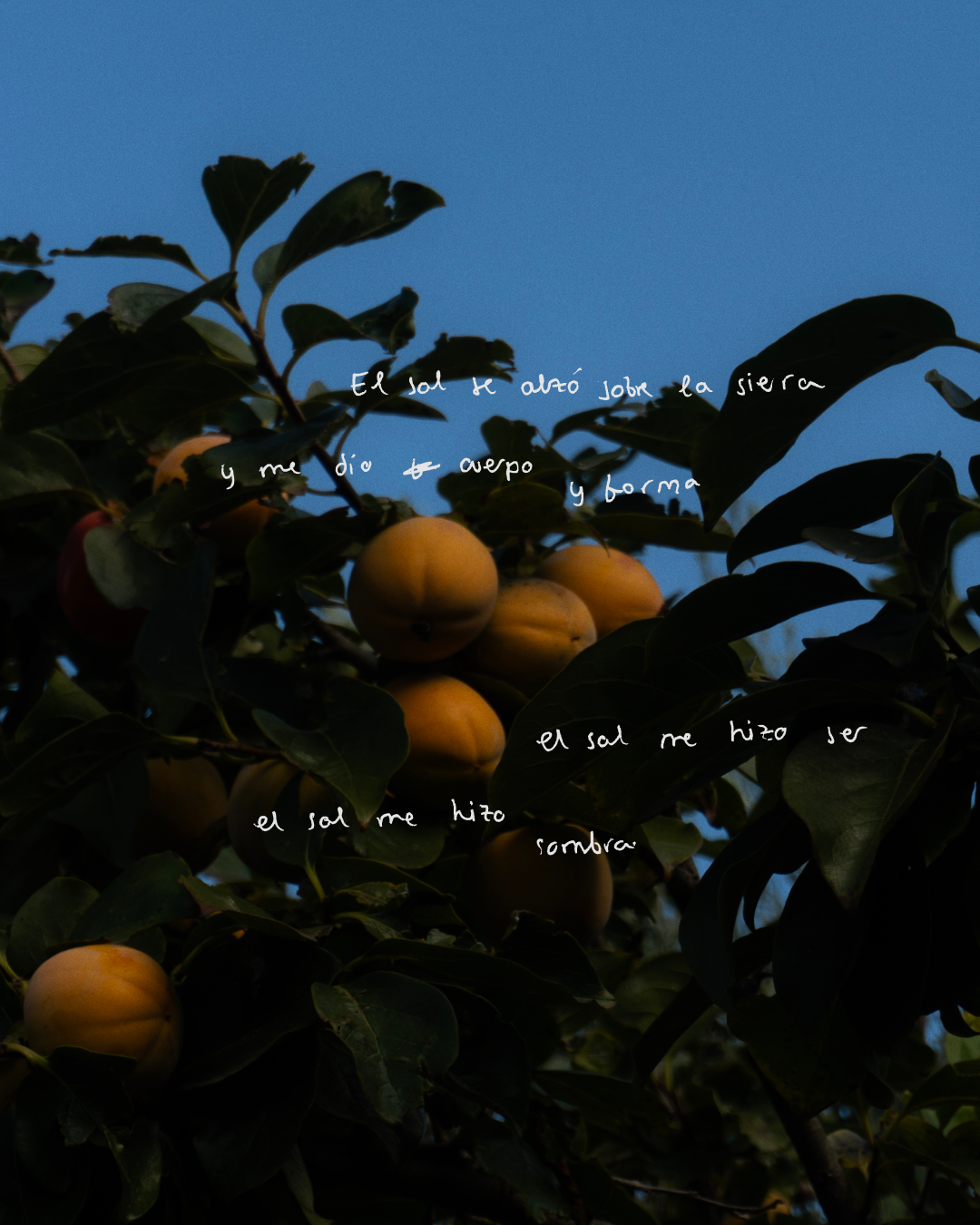

Soy sombra

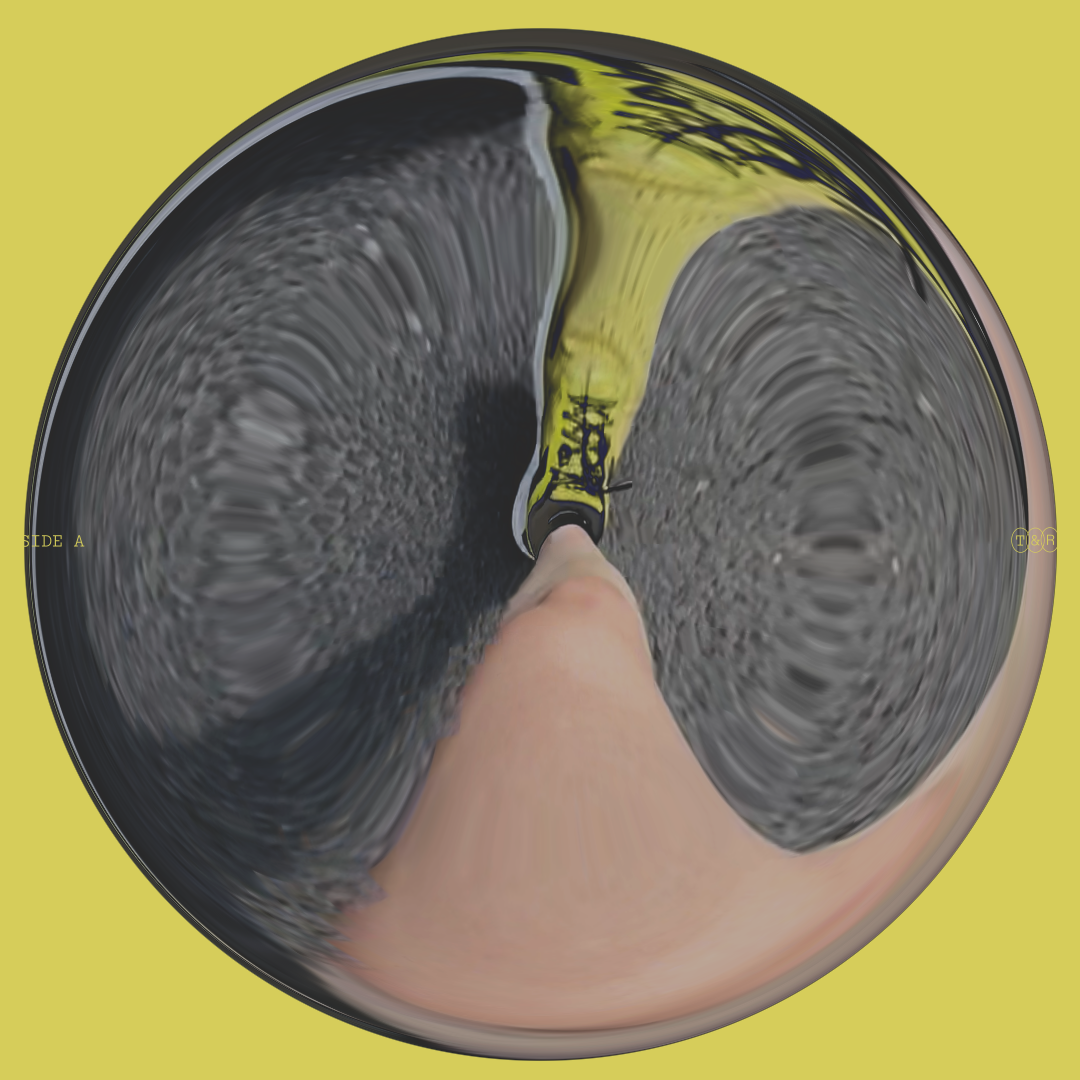

Last week I shared on Instagram and YouTube something I’ve been thinking about doing over the last year, a way to combine a few of my passions into a single output: running, writing and videography, a visual poem.

When I went to Mallorca for a few days on a solo trip at the end of October, I did plan to record some content, but I didn’t necessarily picture what I would end up doing with it. The creative process is often like going for a run in a new place: intuition and fascination set the direction that takes you to an unexpected destination. The final picture, the poem, the movie, it’s all just made of traces, footsteps, sights, things that you didn’t know you would find but that you were drawn to.

“Soy Sombra” (translated as “I’m shadow”) is a story about shadow and self, about how my body loses its shape through movement, my shadow being the only thing that remains, the presence attached to the land, a traceless trace shaped by light.

Hope you enjoy!

The spiral of affirmation

I was leaving the gym on Tuesday, as “Burning”, one of my favorite songs by The War on Drugs, was playing; and as I heard these lyrics, I felt something moving inside me:

“Cross the bridge to redefine your pain

When the answer’s in your heart”

The answer couldn’t be clearer, and all the doubts and questions I’d had the last few weeks dissolved in a muted sigh and a sense of liberation I hadn’t felt in a long time.

I didn’t have to look any deeper; the answer was no. I was not going to run that marathon in December. Not because I couldn’t, not even because I didn’t want to. I decided not to run that marathon because this time I decided to decide.

It took getting ill the weekend before to let myself pause. Not running, not writing, still loads of overthinking because, annoyingly, I can’t escape my own mind. That pause helped me realise how much I needed not just to rest and chill, but to escape the loop, the spiral of affirmation I’d been digging throughout the year.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a bit, you might know that this is something I’ve mentioned before. Despite my self-awareness, and despite knowing I had to stop, I did not. When, two weeks ago, I bought the Valencia ticket on a whim, I carved another segment on that spiral, another journey, another goal.

There was impulsiveness in that decision, and the motivation I had to do it wasn’t even mine at all. It was a product of the external hype, the invisible pressure you create when most of the content you consume is people doing 10 marathons a year. It makes your insecurities arise and makes you question whether you are doing enough, or whether you could do better.

After deleting Strava and Instagram from my phone for a couple of weeks, I stopped caring about my position out in the world as much as I used to. This change naturally raised questions about my own identity and the decisions I was making, including this one.

Since then, I’ve been exposing myself to negation, to the emptiness that being is; to not moving towards something, and to exploring the immensity of my soul freely.

Stones in the path

The 23rd of June this year, as I was leaving the studio, I got a message from my mum that I had been expecting for the last month: my grandad was now gone.

Right after coming back from Italy, I booked a flight to Spain, knowing that could be my last chance to say goodbye to him, and it was indeed. I hugged his skeletal and gaunt body, always covered in a suit he’d tailored and sewn himself, and I slowly walked out of the room in tears, knowing that the touch, the smell, his voice would be forever gone, knowing that that was the last time, facing the implacability and cruel reality death holds.

Every year, my grandad would celebrate his birthday by taking all the family (+30 of us) to a stone-wrought village near our hometown called “Pedraza,” where we would have a big lunch of roast lamb always in the same restaurant. Throughout the years, the pictures of the family standing on the stairs of the restaurant have grown in number but also in age — some of my cousins’ girlfriends and boyfriends are gone, new ones appear, babies are born, and our faces show that time does pass.

Since I moved out of Spain, in few years I’ve attended the birthday occasions, but I couldn’t help having a recurrent thought every 14th of September: “This year could be the last time we celebrate this, yet we don’t know.” That time happened to be this year, and that day I already had something scheduled in the diary: Copenhagen Half.

Since I started running more “competitively” over the last 2 years, I haven’t really raced or trained for a half-marathon the way I’ve done with full ones; having my best time for the half during the Boston Marathon, I knew it could be a distance I could perform well in — long yet fast.

After realising with Boston that the mental strategy of saying to people “I’m doing it for fun” to avoid facing the shame of a possible negative outcome (that no one really cares about but ourselves) didn’t serve me, I decided to set a goal and to say it out loud. I wanted to be accountable, and I wanted to see what would happen if I didn’t get what I wanted.

Goal A was to get a sub-1:25, goal B was to at least get a PB, which I was pretty sure I had, but above all there was something else: honoring and celebrating my grandad, something I didn’t talk about and wanted to keep silent to myself.

One of the things I brought from home when I moved from Spain was the book he wrote with his memories, titled “Even stony paths can be walked.” (“Los caminos con piedras también se andan” is the original title in Spanish) When he was in his late 40s, he had surgery that went wrong and left him limping the rest of his life; however, that was not a reason for him to stop — he would spend most of his days walking around town, doing things here and there: contributing to the community in his church, stepping into the tailoring shop my uncle now owned, having a boiling hot cup of coffee in the bar, and slowly making his way upstairs to the flat they used to live in.

He was my sign of resilience, and I knew despite the course being flat and “just being a half,” I’d need that. I’d need to remind myself that even stony paths can be walked. So I grabbed a Sharpie Kurt happened to have and wrote that on the sole of my fresh pair of Nike Vaporflys the day before the race. I started to cry in the lonely room of my hotel as the sun was setting over the water, realising that I hadn’t processed the loss at all, realising that you never really do; but knowing that I’d have his spirit in the race and making my footprints his calmed the tears with a smile.

A dark cloud approaching across the horizon as we left the hotel foreshadowed the torrential rain that didn’t settle until the end. Molly and I walked together towards the start line, already drenched and soaking wet. I felt calm and easy; complaining about the weather is nothing but a waste of energy, something out of my control that my annoyance wouldn’t change.

After 8 km in, the mental battle began; I went out way too fast, and keeping up the pace was getting hard: the puddles, the tunnel vision the weather was creating, my stomach playing funny games, the expectations I had set out loud, the possibility of not getting what I wanted… I couldn’t find anything positive to hold onto, and at km 12 I almost decided to stop, walk away, and cry. I felt like a child who was sad and couldn’t get what she wanted. I felt the emotional heaviness from last night. I questioned myself why I was doing that again and again, and although I couldn’t see what I wrote on the trainers, I knew I had no excuse. I might not get what I wanted, but I could still fight, I could still keep going. So I collected my shit and emotions and kept going until the end, easing down to then pick up the pace again.

I crossed the finish line at 1h 25m 9s, leaning on my knees, dropping a tear on my way back to get my bag. I looked at the sky, still grey, and I knew he wasn’t up there, he was here, in this stony path we call life; sewing a suit, writing a story, playing his music, forever alive.

To let the skin shed

I’m writing this from an old wood dining table in a castle in Wales. I’ve been postponing this post for weeks now, and it kinda feels weird writing about it now, so I’m just going to start from the beginning and let myself ramble over the keyboard.

Almost a month ago, I started having a subtle pain in my ankle and, despite not having any races coming up, I immediately freaked out. I decided to take a week off running to prevent it from getting worse. While in the past I would have ignored the pain until it became unbearable and turned into an injury, experience, but also an internal impulse, made taking this decision quite easy.

Without realising it, after doing the 54 km at URMA, I kept my training volume as high as it was before. Going for a run every morning had become an automatism that I wouldn’t necessarily enjoy every day or even feel grateful for. Although exercising every morning is something I need to get going and feel good throughout the day, I felt like I was trapped inside a persona whose personality is entirely… running.

I’ve thought about this many, many times, especially reflecting on how lately almost every interaction I have with my colleagues and friends becomes a running conversation. All my interests in books, art, literature, music, and photography seemed to have been left standing in the wardrobe the day I decided to put on the “runner costume” I’ve now been wearing for a while.

Those things were still there, and I guess they were that internal impulse that made it so easy for me to go, “You know what, I’m just not gonna run, and I’m gonna commit to it.”

During that week, I did a bunch of swimming, cycling, HIIT, and strength workouts that reminded me how much I love other sports and how fun it was to be able to do them all.

When I got back into running a week later, it felt like I was running again for the first time. It was as if I’d just been given a pair of fresh new legs, as if I’d just tapped into the magic that newbie runners feel, the thing that makes them obsess over the sport.

Despite the gratitude and fulfilment I felt, that thought stuck in my head. It served as a reminder: I’m much more than a runner, but I do need to shed my skin every once in a while if I want to keep it that way.

To let the skin shed.

To let pause propel the future me.

Like a fly stuck on the glass

It’s Monday, the 30th of June, and we’ve reached over 30 degrees—I just noticed when I left the cool bubble the studio is.

There’s a fly stuck on the glass of the kitchen window, as big as a queen bee, as black as carbon, as hideous as the beetle Kafka imagined. It slides over the glass surface, bumbling, buzzing, certain and stubborn in believing that there is nothing between the kitchen and the garden but a transparent illusion, a magic trick, a trap that entangles her in a vicious cycle where the continuous headbump proves her conviction of freedom but also her ignorance.

I open the window and luckily it doesn’t take her long to go. How pathetic. How much I can relate, though. No races ahead, just running over this glass, hitting a fake sense of freedom, feeling sticky, feeling stuck, hitting my head to get to the other side. No one is going to come open a window for me, no one is going to come draw me a horizon line, no one is going to come set me a place I have to run towards. Isn’t that freedom then? Maybe I just have to stop hitting this invisible delusion and just lift off... and fly.

Intentionally, no

A couple of months after moving to London, my colleague—then and now friend—Alice mentioned she was going to run ‘The Hackney Half’. I had no idea what that was, but it sounded like a good goal to have for the new year and a new way to connect with the city I was now living in, so I signed up.

Despite having participated in races when I was in school, during my early adulthood I was completely hesitant about the following things: signing up for races, running with people, and having Strava. Covered with a persona I’d built on the values of toughness, solitude, and emotional neglect, running was the ultimate form of expression for that character.

Moving to London, though, somehow pushed me to open myself to trying new things and breaking my self-imposed boundaries—and deciding to do a race for the first time in more than a decade was one. I knew that, deep inside, the real reason not to do races was fear. I was very good at going out every morning and challenging my own PBs on a regular day without needing a bib or spectators, but I was indeed scared of putting myself out there, on a start line.

I ran my first Hackney Half in 1h and 35mins. I recorded it using the Nike Run app (because it took a bit longer to break the Strava rule). That experience got me in, and I started signing up for more races, one after another.

This year, having had the chance to run Hackney again—since my friend Luis offered me his bib—I chose to say no.

With running becoming such a massive trend, and London offering all its potential for brands and communities to throw events every single day of the week, I’ve spent the last year trying to take part in as many things as possible and connect with more and more runners. These platforms and events have led me to meet amazing people, make new friends, and spread this project—but they have also increased that FOMO I spoke about in the last post.

I want my running practice to be intentional, not a form of following up—to run with intention is not just about working toward specific races and goals, but about turning every run into a sacrament, not a mere act to accumulate mileage, get some free merch, or appear in someone’s Instagram. To run with intention is to ask yourself ‘why’ before you leave the house. To run with intention is to sometimes saying ‘no’ to running.

On Feet — Offline

I’ve barely rested since I got back to Boston; both my body and mind have gotten used to this relentless rhythm that favors impulse and disinhibition—saying yes to every single plan, desperate to fill my time doing things or just seeing people, vicious with FOMO and addicted to being constantly online, to having a say, to being everywhere.

It has reached a point where I’m overwhelmed. I am tired of running, I am tired of the performance, I am tired of proving myself to myself.

With the clouds taking over after a week of sunshine bliss, and having spent the weekend socialising, drinking more than I’m used to, and going to bed late, I needed this last day of the bank holiday fully for myself. I had to get out of the room where I lock myself in front of the screen, writing for hours and hours and wasting time in between.

Out in Kent, behind mansions and golf courses where middle-aged men carry bags full of heavy clubs, there is an entangled network of small trails and paths. They are like ant tunnels under the soil—narrow, hidden amongst trees, with small wooden gates and different types of locks.

The bank holiday has kept the rest of the mortals in bed, I guess. I cross fields of quiet orchards and dark woodland passages where the leaves canopy the sky in a vivid green cloud. The breeze keeps me cool all the way. There are no beeps or buzzes, just birds singing, the tap-tap of my steps on the ground, the silence of the air, the stillness of the present moment.

The time I spent on my feet is the time I spent offline—an ode to quietness, a praise of presence.

Finisterre

Up in the north of Spain, there’s a small village named “Finisterre”. The name means ‘The end of earth’ (Finis – end, Terre – earth). I remember Mum telling us about that every time we would travel around there.

We were taught in school about America being discovered by Christopher Columbus—one of the narratives that perfectly exemplifies white supremacy in history and in culture. As I’m about to cross the Atlantic on my way to Boston, and Amanda messaged me saying “will be supporting you from across the pond”, this came to my head.

I’ve been to America three times already, and this will be my third marathon, but crossing the Atlantic this time feels more than ever like a step into the unknown—a discovery I’ve been picturing in my head over the last six months, that will most likely be something else I don’t yet know.

Although I’ve watched videos of people doing the marathon and documenting it, I’ve tried not to get too familiar with the course on purpose—to instead surrender to it and let it surprise me on the big day.

Discovery has always been one of the values and motivations that have guided my running practice; we run in places, and those places are traces of history, natural catastrophes, and human victories. Those places are layers of soil and time. Those places may already exist, but they only become tangible to our consciousness when we run through and past them. Some have the vanity to conquer them and consider them their own—setting flags and drawing borders—but others, we are just constantly seeking. And in that constant seeking, the horizon continuously expands. In that constant seeking, there is no Finisterre, there is no finish line.

The Hills and the Heel

I left Hilly Fields with a smile, top off, dripping sweat, glowing confidence. That was the best hill session I’ve had since I started doing them for this block. The session is simple – 3km easy to get there, followed by 8x repeats on a 300m hill with a gnarly bend, floating on the way down, and getting back at (supposedly) an easy pace.

On the last kilometer, I started feeling my right calf tighten, like my Achilles had turned into burning iron; I slowed down a bit and continued to get home. After 3 months of a long block with no injuries or niggles at all, I expected this to happen. I wasn’t too worried—I’ve been here before, and I knew this wasn’t particularly serious—but the line between it being a niggle and turning into something else was too fine, and with three weeks left before the race, I couldn’t risk it all just to satisfy my impulse to run.

I may have needed this niggle to pause and slow down. I may have needed this as the arrow that hit Achilles, making him die. Almost invincible, when Achilles was a child, his mum dipped him in the river Styx (one of the Greeks' underworld rivers) to make him immortal, but as she held him by the heel, that would remain as his only vulnerable part—the only one that could lead to his death. It was Paris, guided by Apollo, who ended up taking down the strongest hero of the war.

It just takes a shot, a hill, an extra rep, an oversight to kill the confidence—to end it all.Before it does, pause and look back—strength can become your weakness, but caring for your vulnerabilities can make you real tough.

Breaking Barriers

As the journey to Boston continues, today, more than ever, we honor the women who opened the doors for future generations to run the course.

After 70 years, in 1966, Bobbi Gibb became the first woman to run the iconic race, finishing in 3 hours and 21 minutes. She had to do it unregistered after the race director claimed that "women were not psychologically ready to run that distance."

A year later, Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to run the race officially, having to battle the ego of a straight white man named Jock Semple, who assaulted her several times along the course.

In 1971, Nina Kuscsik was officially recognized as the first female winner, becoming a crucial figure in enabling women to participate in other marathons.

Today, we celebrate those who, with guts and bravery, stood up for the future of women in the sport—those who broke not just records but the barriers of inequality. Those who fought through performance, showing the world that being a woman means strength, courage, and determination. Those who defied outdated notions of femininity.

Because when women race, we don’t do it against each other, but against something bigger. With each relay, we pass the baton to future generations. With each finish line, we break a wall.

Extended article coming soon in the next printed zine.

In the meantime, pace in peace ✌🏻

The Stuff

How many times was I going to say that again?

“Yes, I want to get out of the city and do trail running more often.”

How many times would I end up spending a Sunday doing the same thing again?

A loop around Dulwich or Brockley. Some sticky oats. Throw some Strava Kudos while I clean my coffee cup. Sit in front of my laptop like a puppet, prisoner of my own discipline and control, and re-create the same tasks from last week.

“Maybe I should change the website of Track&Record.”

“Maybe I should have gotten rid of the sofa and gotten an armchair instead.”

“Maybe I should think about where to eat next weekend when I’m seeing my friend.”

How many times would I excuse myself from plans, saying, “Yeah, sorry, I can’t go because I have to do some stuff”? What even is that “stuff”? Isn’t it just a strategy to break the day into bits that don’t really mean a thing? Three hours of the day are now gone, and I haven’t done much apart from writing down to-dos I will end up delaying—just spending time writing more tasks instead.

How many times was I going to say that again?

“Yes, I want to get out of the city and do trail running more often.”

Well, why don’t I just do it today? Why don’t I forget about “the stuff”?

Training has been a bit boring this week, so maybe I just need to switch the scene to find the joy of running again. I knew a week off my marathon training wouldn’t change my performance, but it could change my mind.

Got a train. Got the vest. Got a route. Got there.

And once I slid—one, two, three times—over the mud, the only task in my head was to stay there: mind my feet, not go too fast, embrace with my ears every bird singing, every leaf breaking, fight that nagging voice wondering if this would be enough for my weekly mileage, ignore the frustration of realizing yet again that I’m terrible at following a map.

I stopped a few times and contemplated the vast green forest, feeling helpless trying to capture those colors somewhere. Maybe sometimes I should just stay on the side, observing, recording with my eye and not with my phone. Guess it’s too late now that my gallery is full of pictures of trees, mud, and moss.

Came back reading Joan Didion on the train. Took a Lime Bike home and devoured some pasta. Posted some stuff on Instagram.

Did that trail run change my mind? Well, I was too tired to even process that.

Did I wake up the morning after thinking about one single thing? I did.

And what was that? Well, it was definitely not “the stuff.”

P.S – I really enjoyed listening to Sam Fender’s new album while running this morning. The first time I listened to it I was like “This sounds very similar to The War on Drugs” and then I found that Adam Granduciel has produced it.

The Setlist

Right after coming back from Spain, having spent the Christmas break there, I booked flights to go back for my dad’s 60th weekend, as my mum was planning to host a surprise party for him on Saturday.

I landed on Thursday night, and on Friday, taking advantage of the time difference with London, I managed to wake up a bit later and go for a fun 10K around Madrid to try my new and first pair of Cliftons, running past some of my favorite places where memories arose as I passed by.

I decided to do my long run on Saturday so I could enjoy my dad’s party without having to think about running the day after. From the moment I woke up, I wasn’t feeling it. I didn’t think about it too much, but at the same time, I didn’t have any excitement to go out and run 24K, as much as I love running at home.

Got a couple of gels, put some bad gym music on, and left the house. It was icy cold, but the sky was beautifully clear. The route I took was the same as last time, and although my legs felt strong, my mind just wasn’t there. I had quitting thoughts I tried to ignore, but I couldn’t stop thinking, ‘Why am I doing this?’

I stopped briefly at km 13, caught my breath, tried to chill, and said to myself, ‘Calm down,’ then kept going. As I progressed, the little demons went away, but by the end of the run, I felt not just tired, but angry and annoyed at my performance and the lack of control over my head… although I didn’t punish myself for too long—I luckily don’t do that anymore.

Later in the evening, during Dad’s party, part of the surprise was that the former members of his rock band brought all their gear so they could play all night long. As in every gig, big or small, there was a written setlist stuck on the floor. Over the course of the evening, I realized they weren’t following it at all—some songs that were supposed to be at the end were played earlier, and vice versa.

That list reminded me of the written splits for a race, and I thought… ‘Well, sometimes you end up blowing the engine right at the end, or those first miles don’t go as slow as you wanted them to.’ And despite having a setlist, a pace plan, sometimes things go off course. What’s most valuable is not your ability to control, but your skill to jam.

Racing against racism

We’ve witnessed many moments at the Paris Olympics this year that will remain iconic in the future. However, it’s sometimes good to travel to the past to remember that some victories have taken longer than four years to achieve.

Mexico City Olympics, October 16, 1968: American athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith take gold and bronze medals in the men’s 200m track final. As they stand on the podium to receive their medals, they bow their heads and raise their fists, each covered by a black glove, while the National Anthem plays.

But there is even richer symbolism in this moment in history: they removed their shoes and wore black socks to represent poverty, and their jackets were unzipped to show solidarity with blue-collar workers.

Even the Australian Peter Norman, who came in second, was also wearing the Olympic Project for Human Rights badge. Yet, the crowd booed the athletes as they came down from the podium.

The race for inclusion is still ongoing, and despite the promise of unity the Olympic Games may represent, inclusion and equality start at home. It can be through protesting or raising your voice, but symbols and stories also have the power to do so.

Alex Zono

Swung by yesterday to have a look atcollection and had a lovely chat with Alex himself. Lovely to see running projects that bring a fresh perspective into the sport, focusing more on stories and emotions over numbers and performance.

00:NOW:00

Two weeks ago, I traveled to Trento (Northern Italy) to join my friend Elena to a small invitational 52km run around the mountains that celebrates trail running in its purest form. The event embraces a “we-don’t-give-a-shit-about-pace-and-time” attitude, keeping it small and local (I guess I was the intruder) and bringing in some cool punk bands for the after party.

Interestingly, my watch died after 34km or so, and it almost felt like it had to be that way. No measures, no numbers, no track, no maps, no real finish line—just running.

Also, my phone, who was in one of the vest pockets got unlocked and a set of black pictures and videos where I can hear my steps and my breathing were randomly taken.Full story coming soon, here are some off-race snaps.

Foundation

A few weeks ago, I started the training block for the Rome Marathon, which will be held on the 17th of March.

This time, as I log the miles, I'll track the myth and foundation of La Cittá Eterna, running beyond history and time to unlock and explore the ruins of this ancient realm.

FOUNDATION begins.

Spine

Things start to get serious when the first half marathon occurs within the marathon segment. Despite the mere 3km difference from my previous long run, there's something about the number 21 that makes me think, 'Okay, from now on, things are just going to get spicy.'

It took me really, really long to leave the house, something that is quite common during long runs that I want to work on, as it’s just me wasting my time messing around and pretending I’m going to find an excuse not to do the hard work.

As I was in Spain at my parents' house, which is located in a small village in the middle of nowhere, instead of taking the main road and looping back the same way, I decided to go one way towards the town, as I knew it would be mentally more fun and pleasant.

I took my phone with me to call my mum once I finish, and as much as I refused to, she convinced me to take one of those little hip bags not to carry the phone in my hand (which I ended up appreciating). Also, to cope with the jitters, I decided to bring music with me again, and I think it actually helped.

The first half of the track was completely downhill, and I was absolutely jamming and experiencing that runner's high... the last 5-6 kilometers were the opposite, though. My hometown, as old as it is, is all about hills, and the last sections of the run, I could feel my legs getting heavier and heavier.

However, when I finished, I felt in pretty good condition, and I recovered better than other days (I suppose all the food I had during Christmas fueled me properly).

Back in London again, I already miss the feeling of fresh air and the various textures my soles experienced back at home; that’s why when I’m there, I try to make the most out of the nature and purity I’m surrounded by.

I haven’t run with music these last days, but I have to recommend the latest Black Keys single ‘Beautiful People.’

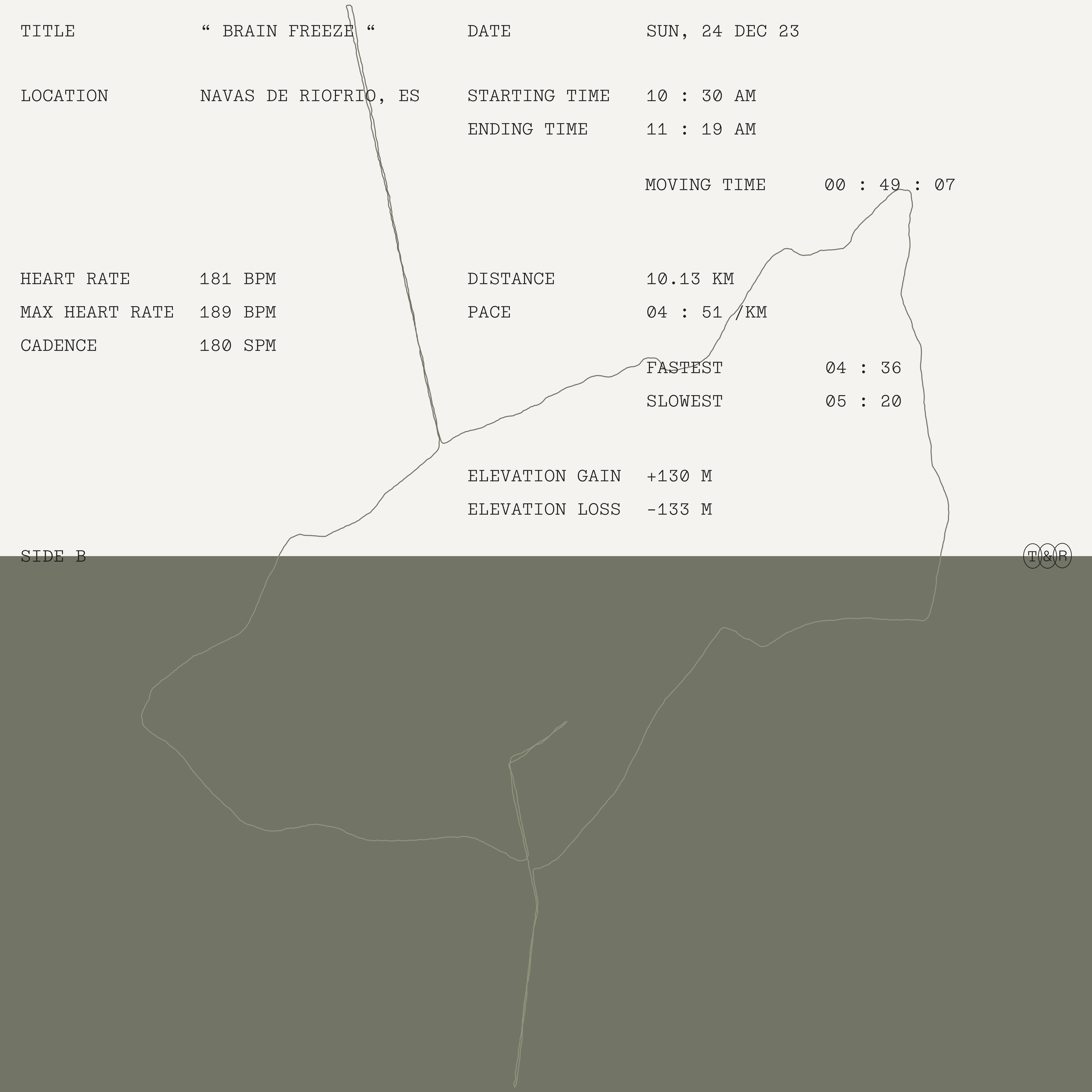

Brain Freeze

This has been the second run since I got home. The change in altitude has been challenging for me since the first run: maintaining pace becomes harder, and the fact that everywhere is hilly makes it almost impossible to maintain consistency with each split, but it also makes the runs more fun.

The air is dry, and the sky is a clear blue, but the ice from the previous night clings to the road and plants like magic crystals, dazzling me when exposed to the sunlight.

Even though I go slower than I would in London, I feel stronger and more capable, sensing my lungs and breath more intimately. Stopping the habit of listening to music during my runs in the last couple of weeks has also helped me connect more deeply with the physical experience itself.

I completed my usual 10k loop, navigating through the dense morning fog. I could feel from the very beginning how the hair on my arms and my forehead were getting frozen, creating that thin crystal crust, like a symbiosis with all the space around.I’m not sure why, but I always loved the feeling of the ice, whether it's against my skin, cracking it with my teeth, or sensing my brain freezing while eating ice cream.

Despite having nothing in my ears but the sounds of birds around, I thought about this Sa Pa album I've been enjoying while working. It transports me to a place like this: ice-cold, dry, quiet, and precious.

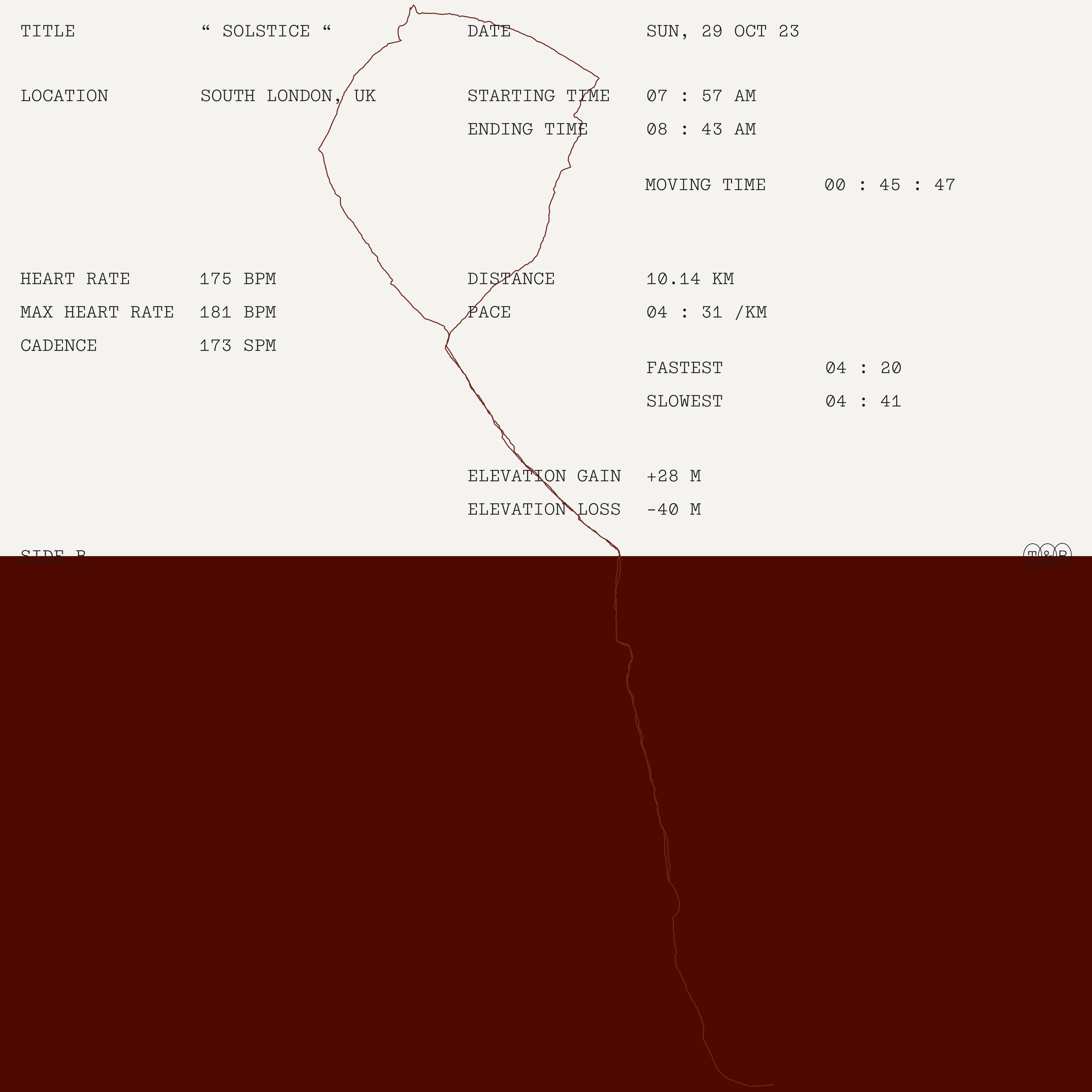

Solstice

I look at the moon, and I understand everything now. The cold has rushed its way in, freezing my face and awakening my desire for speed.

I think about the flat fields in Spain where I belong, where everything started and everything will die.

I think about the bull. I think about the symbol it has become through the myths of our ancestors. Its horns point to the sky with their lunar shape, announcing an eternal cycle of death and resurrection every 3 days.

I think about the bull and the moon, and now I understand the words of Lorca.

I think about the bull, and something awakens, the relics from a past I haven’t lived now appear vividly in the touch of my skin, in the sense of my spirit.

A call for silence, a call for solitude, a call for running

This time there is no music, but Joseph Campbell's first book on mythology, for those who want to transcend the physical and historical.

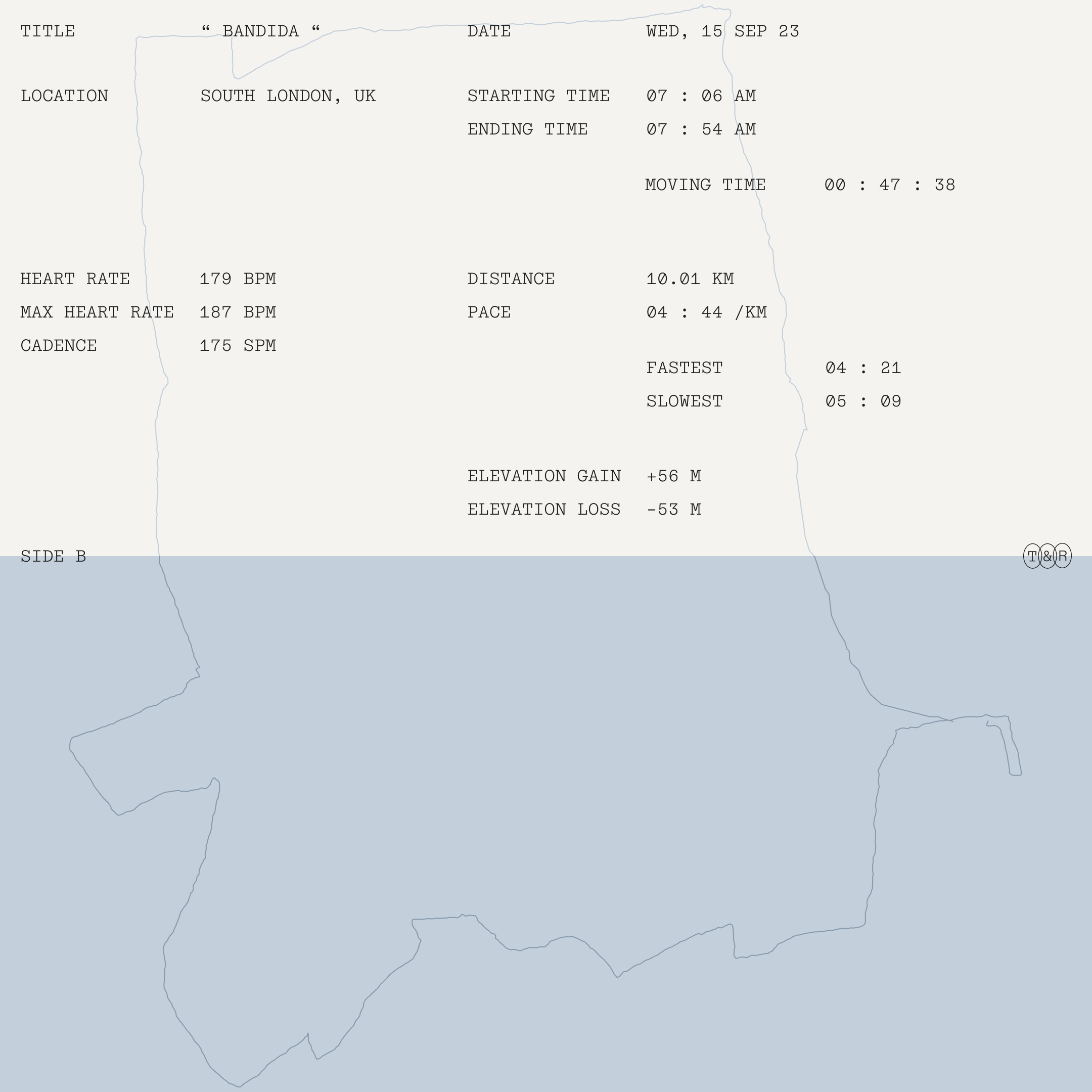

Bandida

I recalled this image Belén took a year ago while we were in Kazakhstan; meditating in the mountains, with no signal, no watch telling me how many calories I’ve burned or steps I’ve done. It perfectly encapsulates how I felt during this run, the duality of the wild and the silent, the inside and the outside, united now as one.

On the outside I felt like a horse that can’t be tamed, galloping from Peckham to Camberwell to Dulwich and back, recklessly, passing through the red lights, squeezing in between the distracted kids that wait for the bus. I had Paco de Lucía on the background taking me somewhere else; a green field as open as my consciousness right now, a field where horses run wild over the gently swaying grass, a field no one belongs to, a field of freedom and peace.

On the inside I felt like a monk meditating on the top of a temple — silent, eyes closed, standing still, enlightened by the detachment and the emptiness of the self. It’s all experience right now; there is no subject or object to distinguish from — it’s all matter made in the moment, raw and pure.

Corrosive

After 10 days in Vietnam with no exercising at all, and almost two weeks without running I guess we can consider this a comeback (not to say the fact that I haven’t posted much as I’ve been working on the website itself)

I did the classic loop around Peckham Rye and Dulwich Cars, and yes, I tried to sped up as much as I could. It felt good, and somehow the pain in the knee seems to be milder now, although I’m trying to start doing again some rehab exercises to prevent the ITB to start hurting again.

Even though I’m focusing more now in CrossFit to be ready for a couple competitions I have ahead, I’m missing running more than once during the week, as well as doing some long distance runs.

I’m already thinking what the next race will be, but for now, let’s let the running virus spread through my veins, I like the high.

I’ve been listening a lot lately to a bespoke playlist Spotify has done for me called ‘High energy workout’ it’s a weird mix, one of the songs that includes is ‘PURE/HONEY’ by Beyoncé, who I don’t usually listen to, but man… somehow this song makes me push hard.

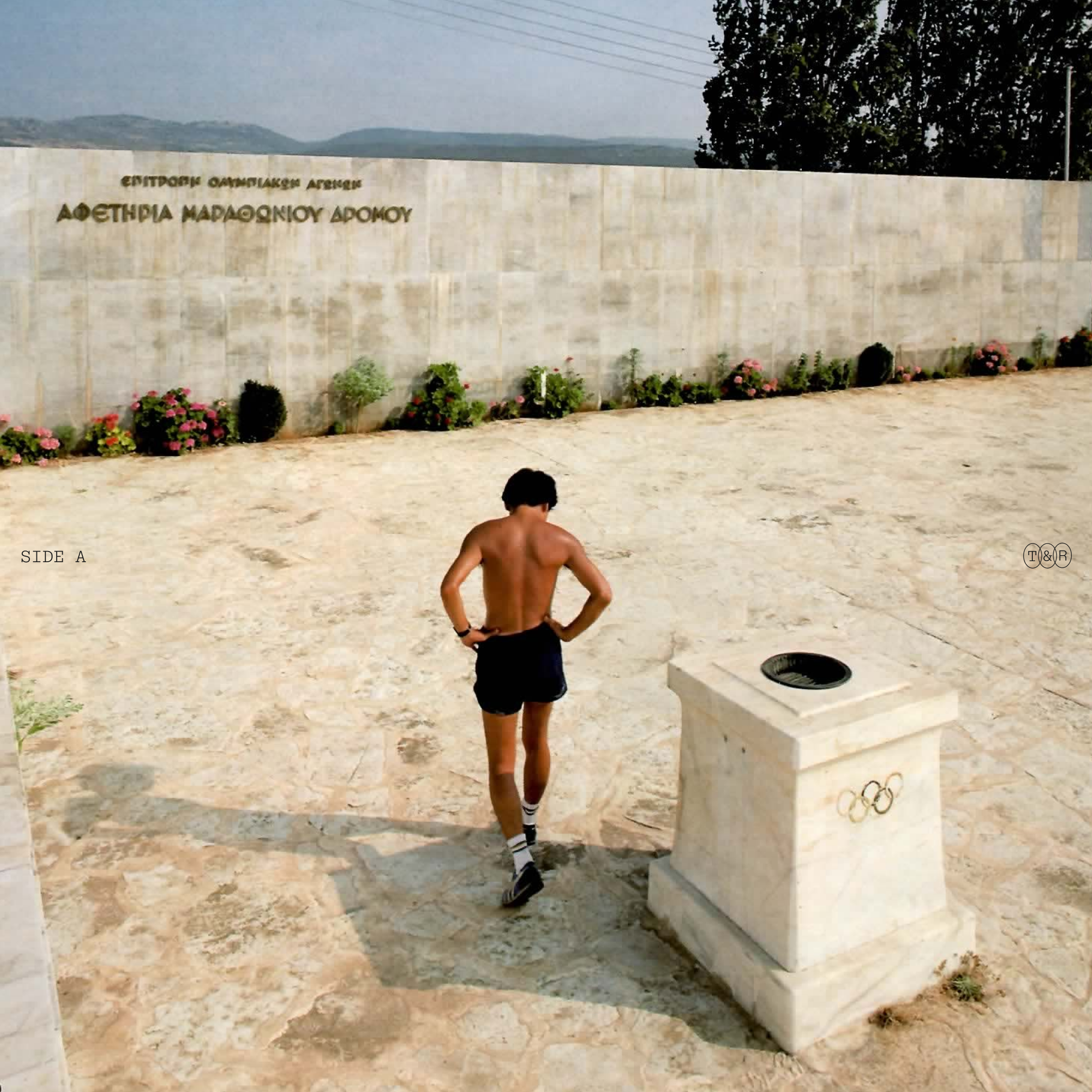

Murakami

In the summer of 1983, Japanese writer Haruki Murakami ran the original marathon track in 3 hours and 51 minutes. However, instead of finishing in Athens, he completed it the other way around.

After receiving a proposal from a Greek Tourism Magazine to visit and review must-see places in Greece, he decided that covering the mythical track could be more interesting. And so, he did.

With no audience, no finish line, just him, the Greek sun, and a photographer following him to document the beginning of his marathon journey.

Photography by Masao Kageyama

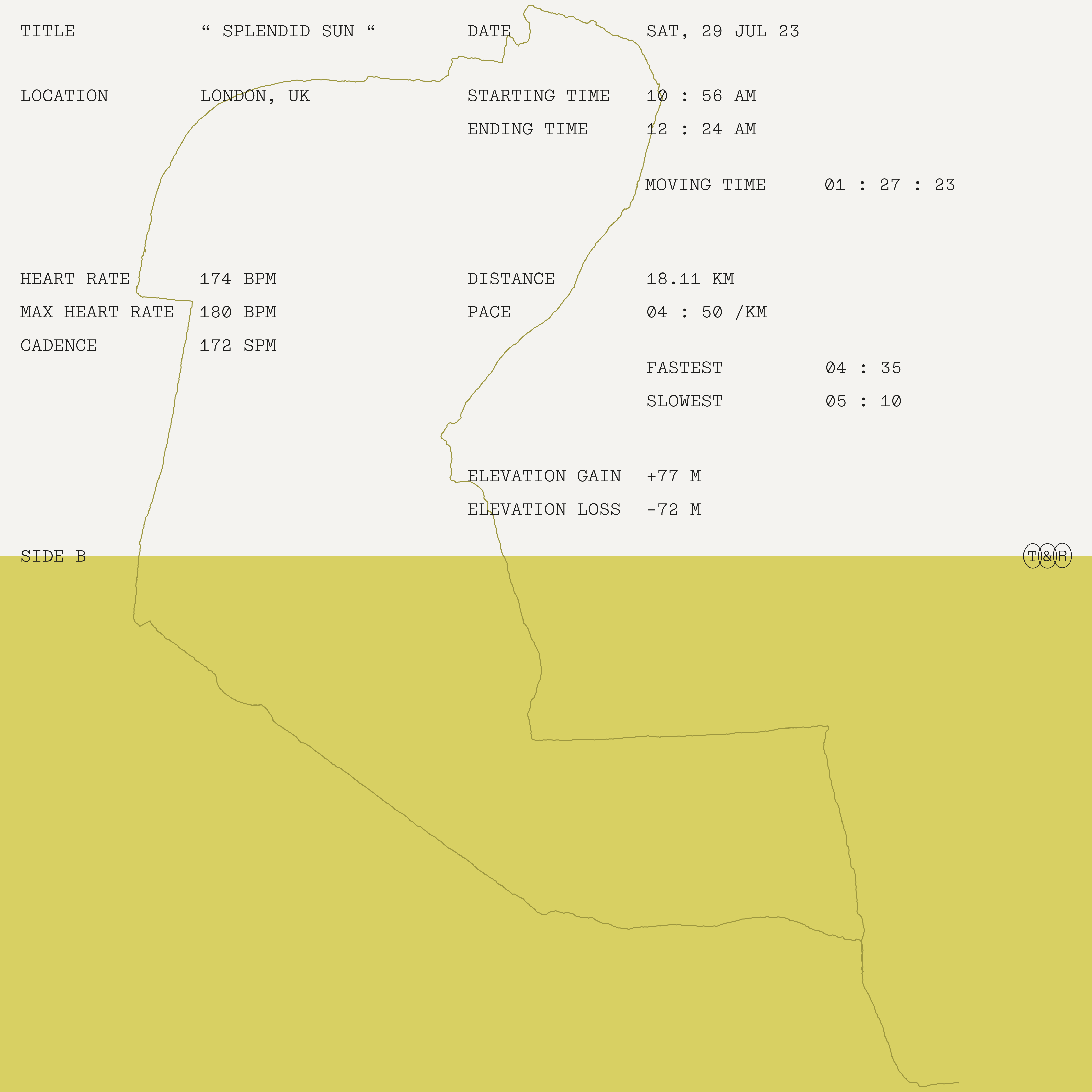

Splendid Sun

In the last couple of weeks, I got back into my running routine. While my knee still doesn't feel at its best, I don't struggle as I used to. However, I've been very cautious about my pace and the length of the sessions… until now.

Running a 5k or a 10k feels nice, but the fact that these runs just become little loops around the same routes bores me a little bit, and that's why I've been missing marathon training and long-distance runs.

I miss getting out of my house and not knowing where I will go or when I'll come back. I miss getting lost in London; I miss knowing that I can go as far as I want.So on Saturday, I was committed to do it, no matter what.

I woke up, and all of a sudden, it started to rain, but surprisingly it was just a 10-minute shower that cleared up the sky afterward. As it happens with every Apple Watch OS update, I wasted a ridiculous amount of time trying to set up my music, ending up deciding to grab my phone because this time I really wanted to have some tunes.

I crossed quickly from Burgess Park to Elephant and Castle without even noticing, and in a quick flick, I was already zigzagging through tourists across London Bridge. The sun was resting gently and splendidly on my skin. Shadows through St. Paul's, where I thought about my mum. Loneliness through the bridges, where I remembered when I used to cycle towards Whitechapel through the superhighway. I got to Westminster and stepped down by the river to get to Vauxhall and back down south.

Logged 18km without even thinking about a single mile, not letting the numbers become a distraction from the joy of just being out there, moving, going somewhere and nowhere at the same time, just pushed by the light of the splendid sun.

I have on loop the new Night Beats' album 'Rajan'

Metamorph

To honor life is to embrace its transitions, the stages in between. It’s the daily practice, the occasional setback, the grey days.

Evolution happens slowly, hidden within the cocoon where the chrysalid remains invisible to the sight.

But to evolve, to metamorphose, one has to dare to show up every day, to be patient, and to trust that there will be another stage; to live life as many and multiple, and not just one.

To desire to go beyond a straight line. To have the certainty of death and yet the desire to forever be alive.

I have back on repeat “History of the future” by The Black Angels

Mango Seco

My dad always keeps a packet of dried mangoes in the glovebox of the car. I had never been interested in it until a couple of weeks ago when, feeling a little nostalgic, I decided to try some.

Now, I have developed a liking for its weird chewy texture that I used to dislike, and it has become my go-to sugar boost before going for a run or workout.Just like that snack brings me back home, this run has somehow become my own 'running comeback.'

Although I had gone for a few runs in the weeks before, this time I felt not only physically strong and fit but also happy and motivated to be back on the road again.I have on repeat ‘VOLVER’, love how unexpected this combination of Tainy, Skrillex, Four Tet and Rauw Alejandro has came out.

RRR

I could be more captivated by the tiny droplet hanging over the surface of one of the leaves of my banana tree plant — the first I’ve ever owned and also the only one.

I got it when I moved into my new house to bring some life to the vast room I know have, but also to test myself whether if I could or not to take care of something else.

After a couple of months I completely forgot about it and almost letting it sit near the window knowing its leaves were turning brown and dry.

I ignored it because it didn’t mean much, until one day that I realised how brutal that was.Borrowing my flatmate's scissors, I trimmed away all the dry parts, watered it, and gave it the name 'Marisa’.

When I returned home last Saturday after my run, which felt terribly difficult, I noticed a tiny droplet hanging from one of its leaves, perfectly suspended, portraying pure beauty and life.I found myself identifying with the plant—sweaty, slightly melancholic due to my recurring knee pain, recalling Bernini's 'The Rape of Proserpina' and its incredible human detail.

How beautiful pain can turn to be when contained and captured in time, like the droplet on the leaf, like marble coursing with blood, like the defeat after the effort, like the constant desire of victory and life.

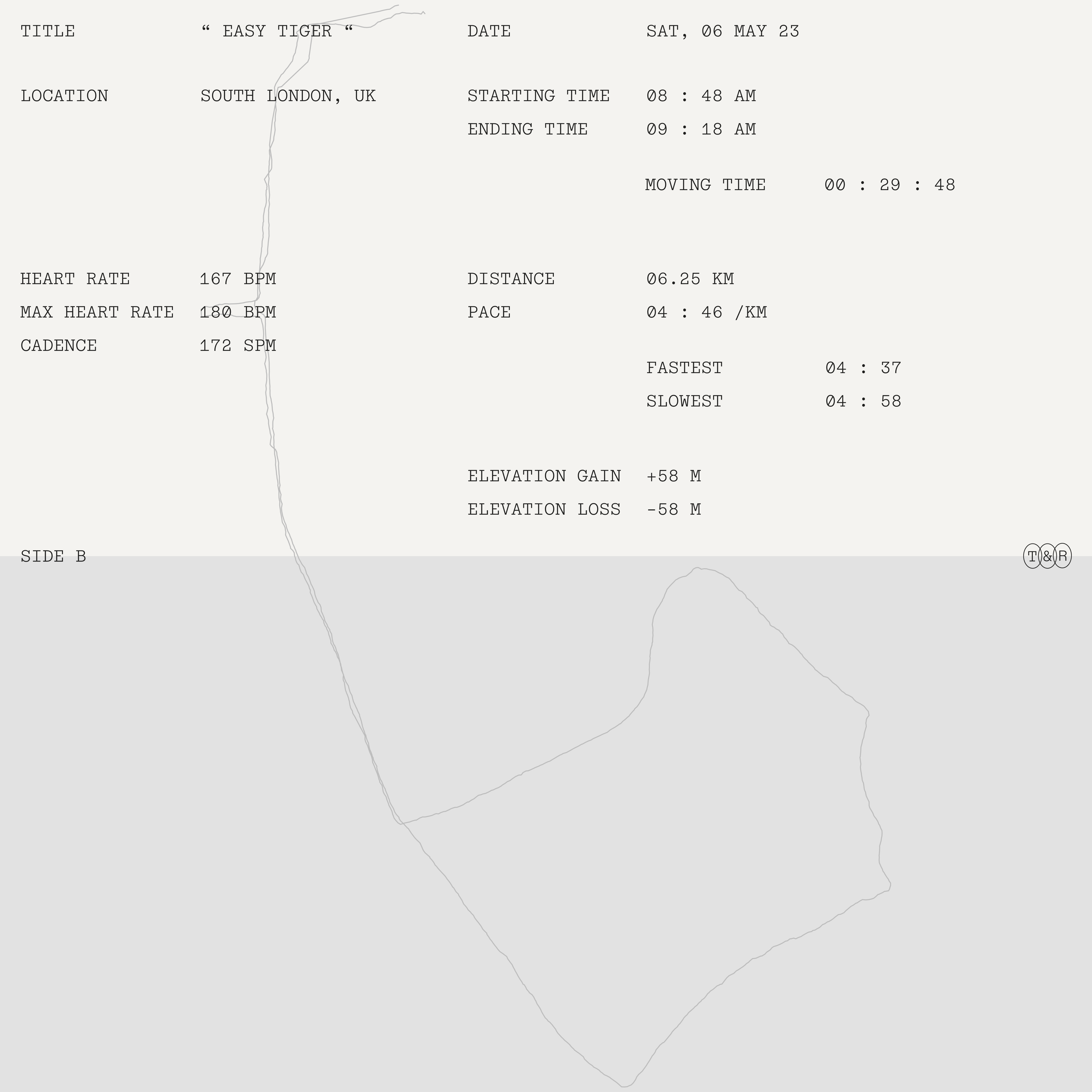

Easy Tiger

I gave myself a couple of weeks without running at all to let my knee rest after feeling pain during my last few runs.

After the marathon, I thought I would experience the 'runner blues' Murakami talks about in his book. It has happened to me before – that boredom you feel after training for a while, the repetitiveness, what the French describe as 'ennui.' I guess that's why I started doing more CrossFit instead of running again. Nonetheless, the truth is that since I got injured and the weather has been getting better, I've really missed running during these past couple of weeks when I had to stop.

As I was concerned about my knee, I went to the physiotherapist and received the same answer I got the first time I got injured: my calves and butt are too weak compared to my quads.

When it comes to lifting, gymnastics, or any sport other than running, I care about technique. However, when it comes to running, something I've always done and naturally enjoyed, I've refused to focus on metrics.

That said, I'm not going to ignore the physiotherapist's words and recommendations, but I don't want to force what comes as effortless movement.

He recommended going for a light run at an easy pace to see how I'd feel. Of course, I ended up going faster than he wanted me to, but I couldn't help myself.

The feeling of my feet hopping on the ground, my hair flowing freely, the speed...

Running connects me with something primitive that has always been inside me.